Flying cars and high-speed rail: strangled by local politics

Deep in the exurbs of the San Francisco Bay Area, billions of dollars are being spent building the future of high-speed transportation.

Between the cities of Merced and Bakersfield, the California High-Speed Rail Authority has spent nearly $12 billion on bridges, tunnels, and embankments (as well as consultants and environmental impact assessments) that might eventually form part of a 500-mile high-speed railway connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles.

And at formerly sleepy regional airports across the Central Valley, a half-dozen venture-backed startups have collectively spent at least $10 billion to date developing "advanced air mobility" (AAM) or "electric vertical take-off and landing" (eVTOL) vehicles—or in plain English, electric air taxis.

Joby prototype aircraft at Marina Airport. Source: Christian Zhang

There are many reasons to start building high-speed railways and experimental aircraft in the middle of nowhere, with safety and cheap land near the top of the list. But the biggest reason is because the communities CHSRA and the electric flying taxi startups hope to one day serve don’t want anything to do with them.

One of the greatest paradoxes of Silicon Valley and California is that they are simultaneously home to the world’s most technologically advanced and innovative companies, and the world’s loudest and most-successful opponents to development and progress.

Flying cars, but not here

eVTOL startups Archer, Joby, and Wisk may have their headquarters in the Bay Area, but they conduct most of their testing further away in Salinas, Marina, and Hollister airports, respectively. Even if the companies are successful in developing a safe and economically viable aircraft, it is unclear whether they will even be able to serve their home communities.

Palo Alto Airport is currently holding community engagement meetings for its Long Range Facilities and Sustainability Plan (LRFSP). It is important to note that this is not a plan for development, but a plan to determine what needs to be planned for development: “The goal of the LRFSP is to determine the extent, type, and schedule of improvements needed to accommodate existing and predicted future needs at the Airport in a sustainable manner.”

Proposed improvements include a longer and wider runway and provisions for a vertiport to eventually support electric air taxis. Attendees at a recent public hearing made it loudly known that they are upset and they prefer nothing to happen. Menlo Park Mayor Cecelia Taylor said in a related interview that she would prefer the “do nothing” alternative.

Elsewhere in the Bay Area, Reid-Hillview Airport may close by 2031 after Santa Clara County voted in 2018 to reject FAA funding for airport safety improvements. Across the US, the number of public use airports has been steadily declining from a peak of over 5,500 in the 1980s.

Opponents of the airport expansion do have a point: aircraft are annoyingly loud and sometimes fall out of the sky. There is a reason why helicopters never became a mainstream form of transport. It is telling that Archer Aviation recently announced plans for its initial Bay Area network depict “Sea Portal Mobility Hubs,” essentially long piers that put landing aircraft as far away as practically possible from the nearby office buildings.

Archer's proposed "Sea Mobility Hub" vertiport at Oyster Bay, South San Francisco. Source: Archer

Let them eat trains

Private airplanes and flying cars may be for the rich, but Californians surely want high-speed trains, one of the fastest, greenest, and highest-capacity forms of transport ever invented, don’t they? The long history of California High-Speed Rail and the questionable engineering decisions made in the final plan indicate differently.

As of mid-2024 the State of California has spent nearly $12 billion—and will likely spend at least $35 billion—on building an “initial operating segment” between the cities of Merced and Bakersfield. Eventually, pending funding and environmental approval, that segment will hopefully be extended to San Francisco and Los Angeles at a cost of at least $100 billion.

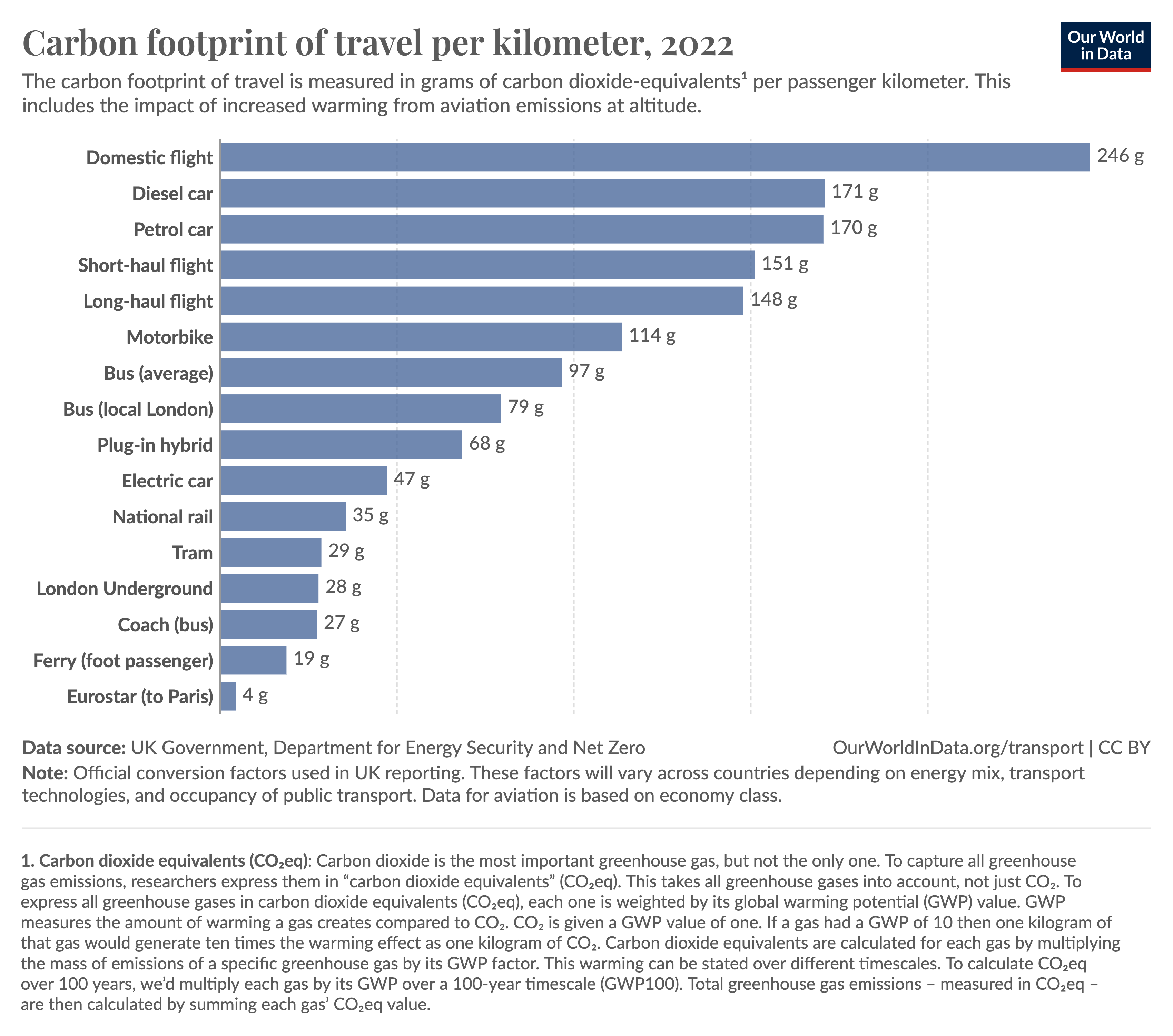

By almost every measure high-speed rail is good for the environment. In the UK, high-speed rail emits just 4g of carbon dioxide per km travelled, compared to 246g/km for short-haul flights and 170g/km for gas cars. High-speed trains will also benefit a lot more people than flying cars. An 8-carriage trainset carrying 500 passengers every 5 minutes equals 6,000 people per hour; an eVTOL aircraft carrying 6 passengers every 30 seconds is just over 700 people per hour.

That hasn’t stopped individuals and cities from trying to block the project, ostensibly on “environmental” grounds. The towns of Atherton, Menlo Park, and Palo Alto (notice a pattern?) famously sued CHSRA in 2008 to try to block the project, arguing that the project would negatively harm the environment. That case resulted in numerous public hearings and 163 court filings, and forced the state to revise plans twice in two years before it was dismissed in 2013.

A content compromise: self-driving cars

If local politics remain allergic to the moderate compromises and expense required for a high-speed future, the future of transport in California will most likely look like the present: personal vehicles seating 1-5 people, only self-driving and electric. Self-driving cars can use existing roads and highways and do not require significant investments in new infrastructure; other than the pesky question of what happens to drivers, there is nothing for lower-c conservatives to oppose.

Self-driving cars are of course still cool and futuristic and will likely lead to safer and faster commutes, but bullet trains and flying cars they are not. They also share many of the same disadvantages as conventional cars: traffic (ultimately a function of limited road capacity, which flying cars solve by going above and trains solve by packing people closer together), suburban sprawl, and environmental pollution from microplastics.

Before the 1800s it would take two days to travel 100km by foot, horse, or camel (contrary to popular depictions in media, horses cannot gallop over long distances). By the middle of the 19th century, steam trains travelling at 60km/h cut that travel time to less than two hours; cars on highways can travel 100km in less than an hour. Today high-speed trains in other parts of the world can cover that distance in 20 minutes.

Faster modes of transport bring people closer together, and more homes, jobs, businesses, and attractions within reach. But in the US, average travel speeds have plateaued since the 1970s; cars, trains and airplanes aren’t getting any faster. It would be a profound shame if we let local politics prevent us from moving past that.