How to lose $108 million in San Francisco

Originally published on Substack.

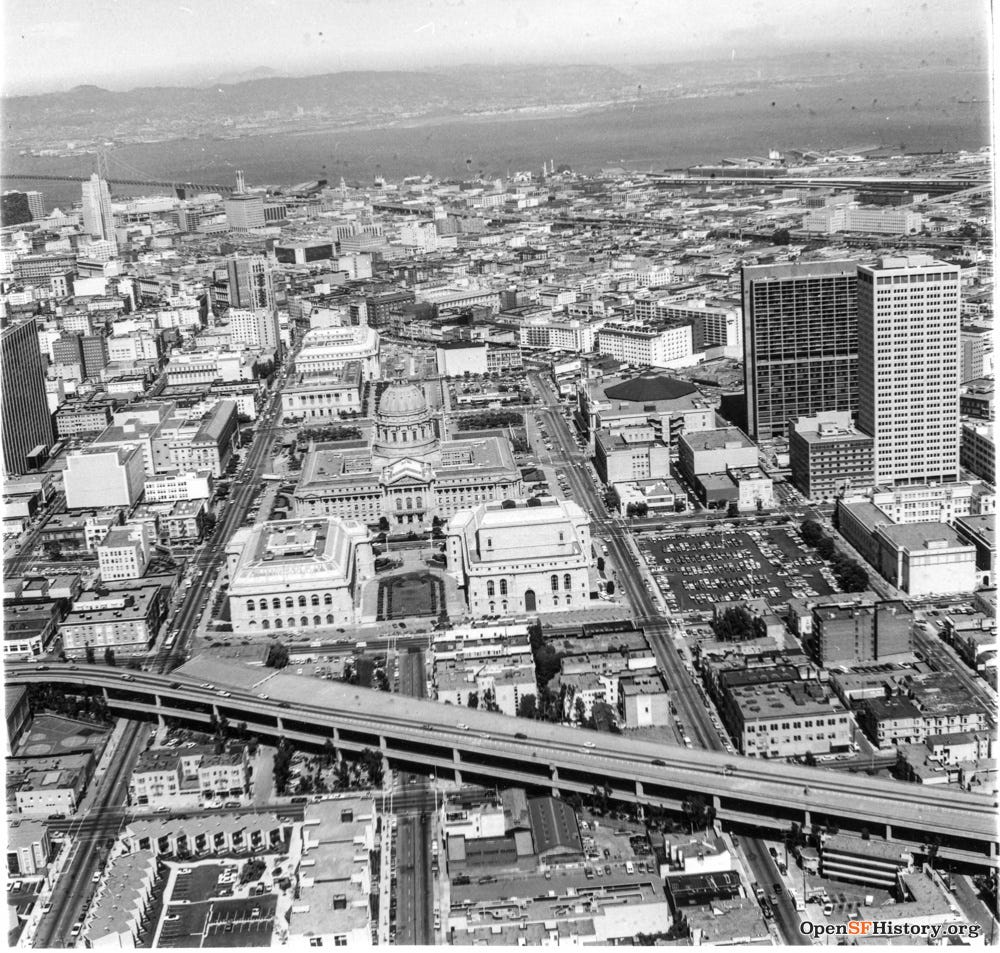

8 Octavia Street, one of SRT's properties in San Francisco. Photo: Author.

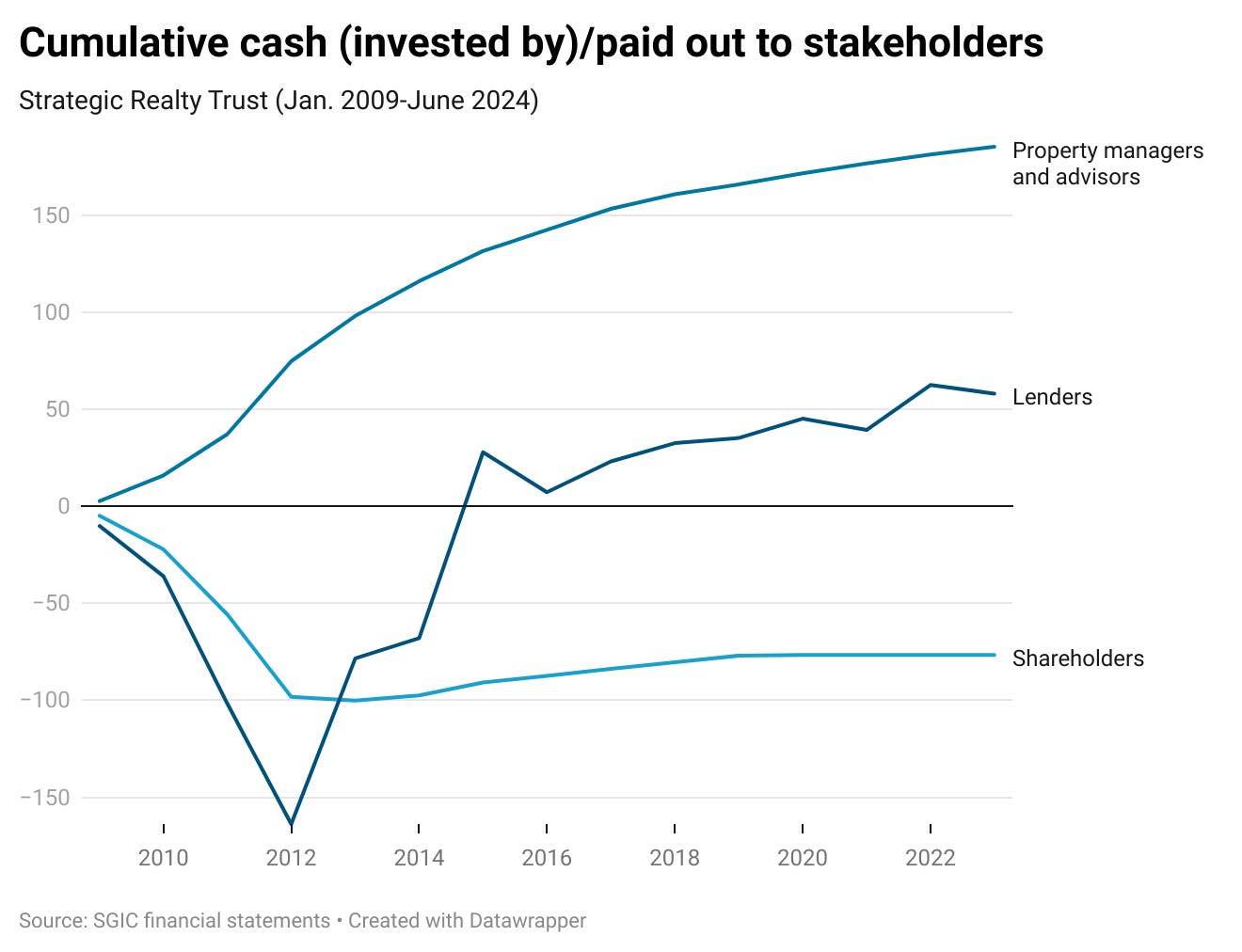

Between June 2009 and June 2024, an obscure, non-traded real estate investment trust (REIT) raised $108 million from investors only to slowly lose all of it buying properties high, selling low, and paying expensive interest rates and property management fees. (Lenders were largely repaid and earned a small profit from interest, while the biggest winners were property managers and advisors.)

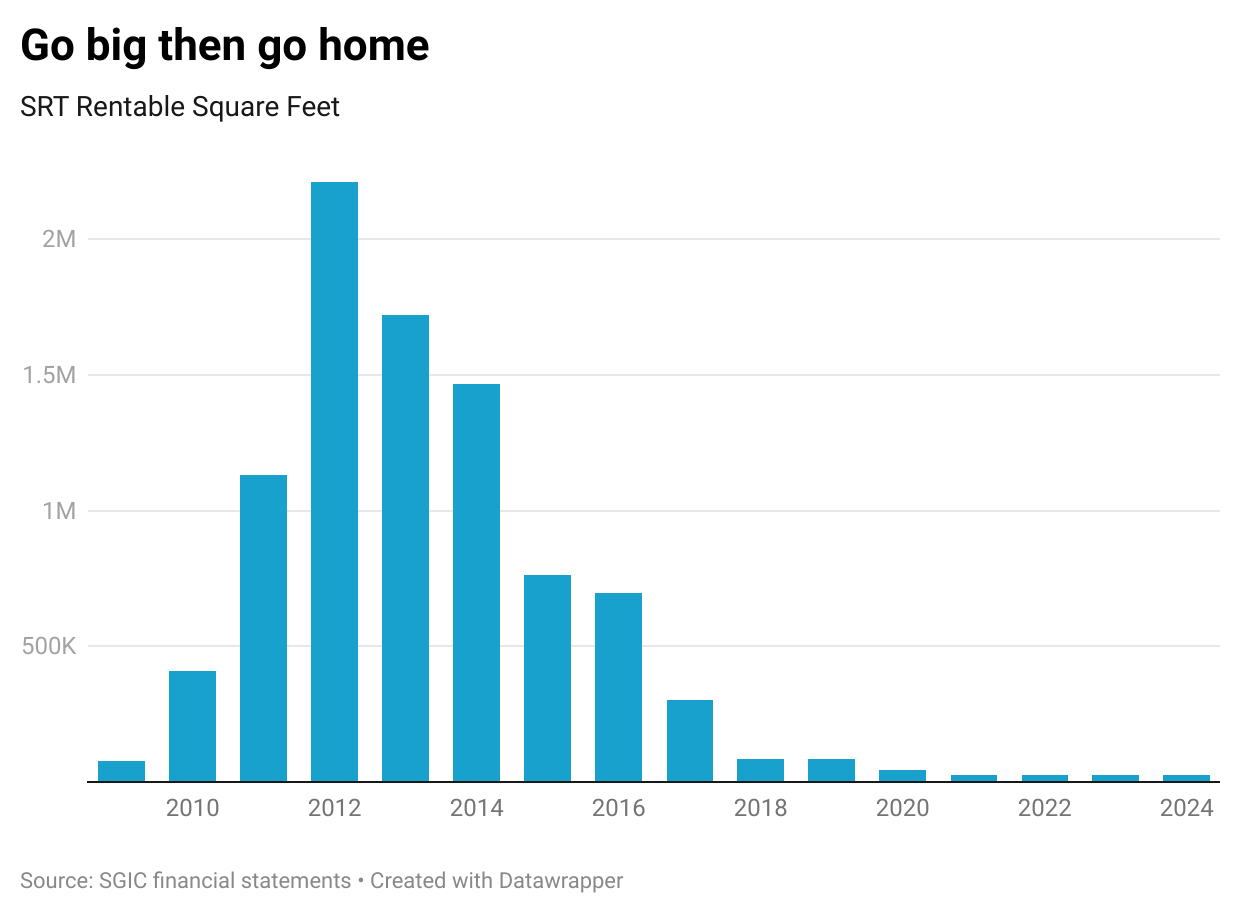

This company, Strategic Retail Trust, at its peak owned 21 properties with a total rental area of 2.2 million square feet. Today, its portfolio has been cut down to just 6 storefronts in Hayes Valley (where I first stumbled upon its architecturally notable properties) and a small strip mall in Los Angeles; the former are expected to be sold next week in a transaction worth $10.5 million.

Few neighborhoods are more emblematic of San Francisco's boom-bust-boom cycles than Hayes Valley. Its architectural style is bookended by Victorian row houses and neo-futuristic condominiums. Its economic history includes chapters as one of San Francisco’s first affluent suburbs in the 1860s, one of its most dangerous in the 1980s, and one of its hippest after it was re-christened “Cerebral Valley” by venture capitalists and realtors in the 2020s. Since late 2022, dozens of AI- and AI-adjacent startups based in Hayes Valley have probably raised billions of dollars in funding.

This is not that story. In fact, this story has almost nothing to do with AI or technology. It is instead about rich valuations in commercial real estate, questionable corporate governance at small-capy companies, and the enrichment of property managers and lenders at the expense of investors.

From June 2009 through June 2024, SRT raised $108 million from shareholders and lost almost all of it. Lenders were largely repaid and earned a small profit from interest, while the biggest winners were property managers and advisors.

Strategic Realty Trust

Strategic Realty Trust (SRT) is a public, non-traded REIT that currently* owns a portfolio of retail properties throughout San Francisco and Los Angeles. The trust trades on the OTC Pink Sheets market under the ticker “SGIC” and as of April 30, 2024, had a market cap of around $430,000.

SRT was formed in September 2008 as TNP Strategic Retail Trust, Inc. as the flagship investment vehicle of Tony Thompson’s Thompson National Properties LLC. Thompson had previously made a name for himself after founding Triple Net Properties, which repackaged and resold tenants-in-common exchanges before the Global Financial Crisis. SRT’s initial prospectus filed with the SEC ambitiously planned to raise up to $1.1 billion, which would have made it one of the largest non-traded REITs ever.

The trust started to accept outside investors in August 2009 and eventually raised $108 million through February 2013. These proceeds, levered with another $210 million in debt, were used to acquire 21 strip malls from Hawaii to Florida totaling 2.2 million square feet at peak.

Red flags started to emerge even before SRT completed its initial public offering. In early 2012 SRT sponsor and property manager TNP started to miss interest payments on previously issued debt instruments; an internal audit revealed that TNP was essentially insolvent, with its liabilities exceeding its assets by $45 million by September 30, 2012. By January 2013, these issues had spread to SRT, with the trust disclosing that it was negotiating forbearance agreements on loans related to six properties to avoid foreclosure. SRT suspended its dividend shortly after.

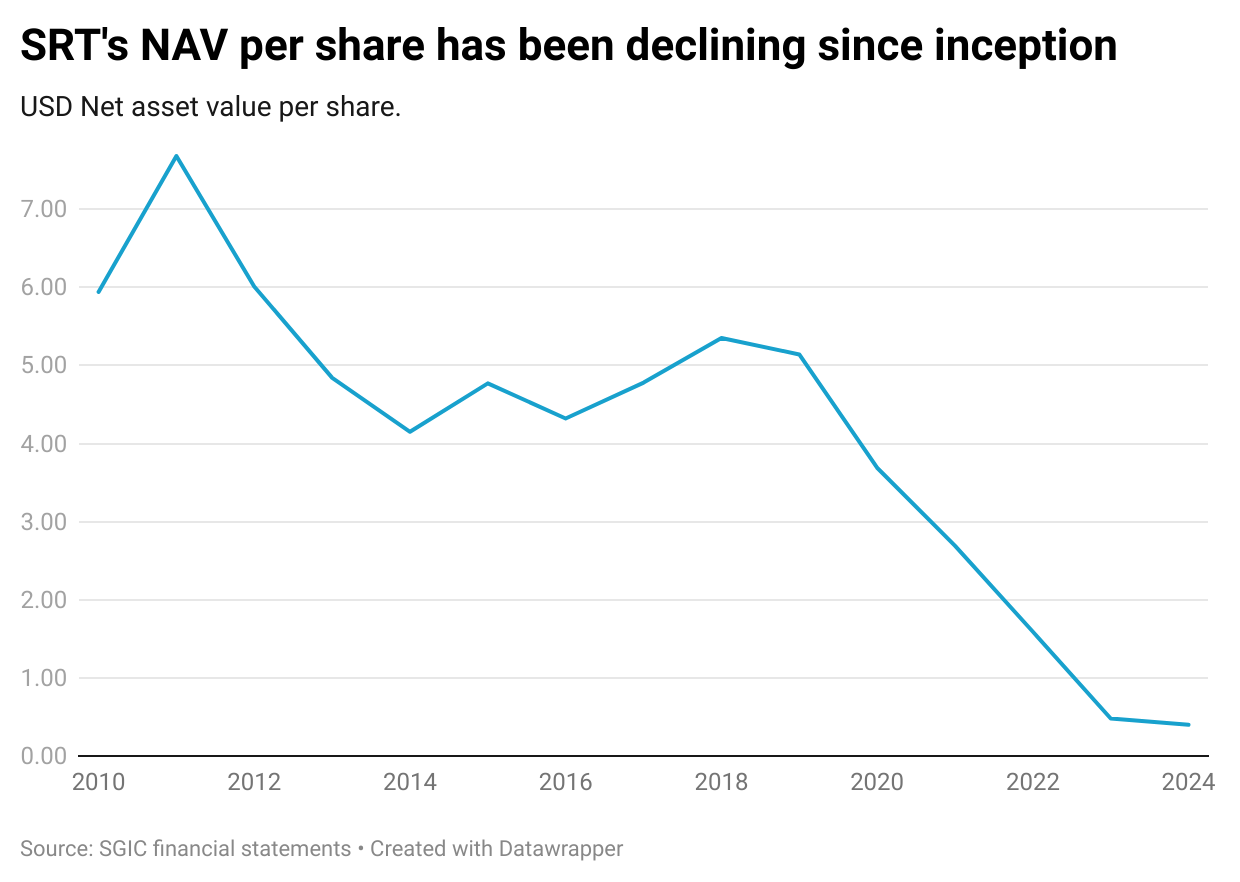

These developments added to already questionable behavior at SRT: paying dividends to existing investors using cash raised from newer investors; selling new shares at below the trust’s net asset value (a practice frowned upon because it dilutes existing investors); and giving broker-dealers a generous 10% commission for sales of SRT shares (compared to 5-8% for “conventional” investment banking IPOs).

Then there was the simple fact that the trust couldn’t even make money. In 2012 SRT collected $23.4 million in rental revenue and lost $17 million in net income ($7 million excluding depreciation and amortization).

SRT’s first chapter came to an end in August 2013 after the board voted to remove Thompson as chairman and CEO and allowed its advisory agreement with TNP to expire without renewal. In Thompson’s place SRT appointed as CEO Andrew Batinovich, whose Glenborough LLC real estate investment fund had significant stake in the trust. It also hired a new property manager and advisor affiliated with Glenborough and renamed itself Strategic Realty Trust.

(In 2014, the Financial Regulatory Authority (Finra) barred Thompson and TNP from the securities industry, saying he had “made material misrepresentations and omissions in the sale of private placement securities to investors.” Thompson was later sentenced to nine years in prison in 2018.)

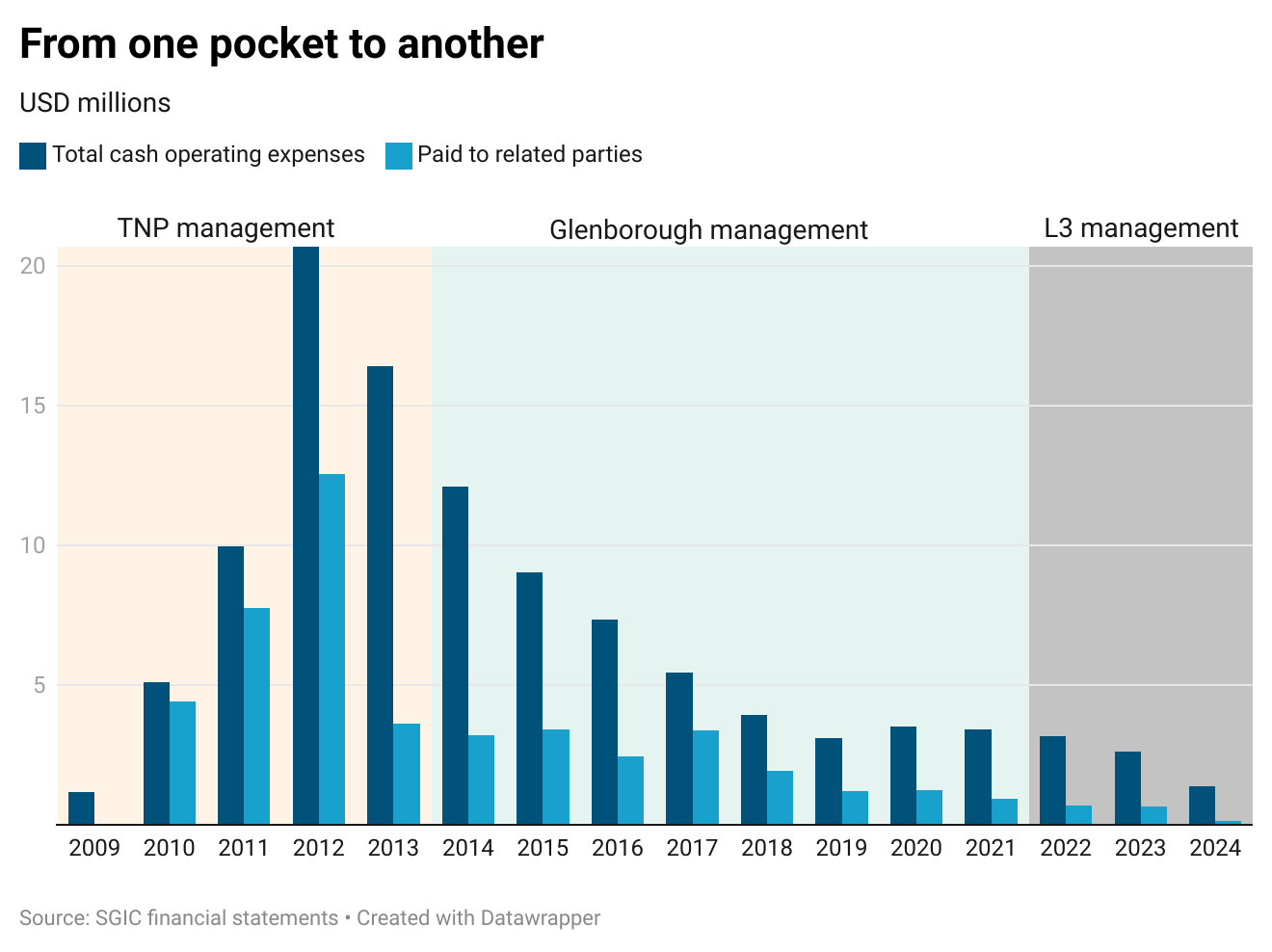

Under the TNP group's management, SRT paid generous management and advisory fees to related parties.

From Retail to Realty

After Batinovich/Glenborough takeover, SRT sold three properties and gave up a fourth to lenders for net proceeds of $22 million, which was mostly used to repay some debt. It also restructured the terms of a loan with KeyBank to allow it to resume paying dividends.

All this while, Thompson was trying to take back control of the company, suing SRT and launching a proxy fight to try to call for a shareholders meeting to elect a new board. The archived letters are delightfully nasty. Thompson’s group, calling themselves the SRT Shareholders Coalition, accused new management of taking the REIT in the “wrong direction” and “wasting shareholder money,” including stuffing the trust with higher expenses to benefit Batinovich and his associates (which Thompson was previously doing). SRT management responded with dramatic letters urging shareholders, “DO NOT BE MISLED BY TONY THOMPSON’S MISREPRESENTATIONS.” The two sides resorted to using color-coded proxy ballots: white for Batinovich, orange for Thompson.

SRT still wasn’t making any money—in 2014 the trust earned $21.7 million in rental income and lost $11.7 billion after paying $9 million in interest expenses and $12 million in operating, maintenance, and administrative expenses. Although Glenborough management resumed the dividend, it was a meagre $0.05 per quarter, or a 2% yield on the $10 offering price. SRT wasn’t traded on any exchange, which made it difficult for earlier investors to sell their shares even at a discount.

All this made SRT an attractive target for microcap activist investors. Between 2014 and 2020 SRT shareholders were sent six separate mini-tender offers by MacKenzie Realty Capital, Inc. at prices around half of NAV. It is generally difficult to find historical transaction prices for securities that are not traded on exchanges, but this gives you an idea of how much of a discount non-traded REITs typically can have.

Glenborough management otherwise made gradual but positive improvements to the trust. It restructured loans to reduce interest payments from nearly 50% of revenue to less than 15% of revenue from 2013 to 2018, and gradually sold underperforming properties at breakeven-to-slight gains. New management also eliminated some of the more-questionable practices at the REIT, including hefty acquisition expenses paid to a related party for “finding” new properties.

Hayes Valley Freeway Lots

Until now, SRT’s property portfolio had mostly consisted of suburban strip malls. In March 2016, Batinovich revealed a new strategic plan in his shareholder newsletter, which included pivoting to owning a “core portfolio of high quality urban retail properties.” Later that year and in early 2017, SRT implemented this strategy through the acquisition of five commercial condos in and around Hayes Valley for a total of $22 million. These were financed primarily with the sale of its existing suburban properties and some debt.

The Hayes Valley properties had an interesting history. These were all ground-floor retail units in recently built low-rise condominiums. From 1959 to 1992, Hayes Valley was cut in half by the Central Freeway running down what is today Octavia Street. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake severely damaged the roadway and Caltrans demolished the section north of Market Street in 1992. This left behind several “freeway lots,” just in time for the construction boom of the 1990s and 2000s.

The Central Freeway in Hayes Valley. Source: OpenSFHistory / wnp28.2776

450 Hayes Street was built on land formerly occupied by the Central Expressway. Photo: Author

SRT’s Hayes Valley acquisition was followed up by three other investments in Los Angeles, one each in Silver Lake, Hollywood, and Santa Monica.

The new strategy got off to a great start. The new urban storefronts cost a lot more (the Hayes Valley properties cost between $1,200 and $1,400 per square foot, compared to around $120 per square foot for a suburban retail complex) but earned a lot more in rent. The most valuable property, 450 Hayes Street, yielded $7.50 per square foot per month in 2017, compared to $1.50 per square foot per month for a suburban grocery store.

The new properties elevated SRT’s status. Whereas its previous tenants included banks and grocery stores, the trust’s new urban properties were home to acclaimed restaurants like A Mano, named one of the Bay Area’s Top 100 Restaurants by the San Francisco Chronicle in 2018. That was also the year that SRT saw its first and last year of profit, excluding gains on property sales, in 2018.

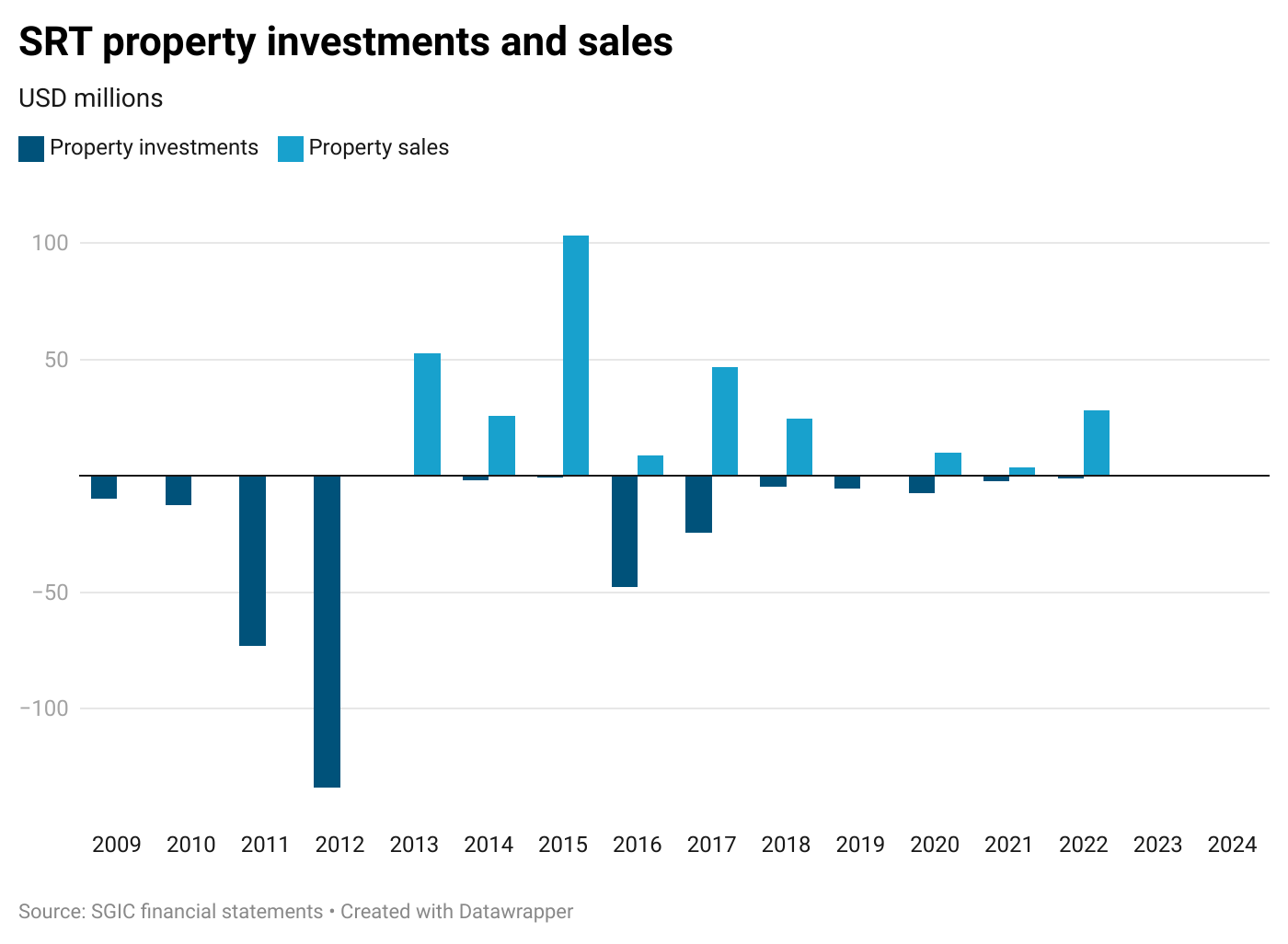

SRT invested a lot in suburban retail properties in its early years, only to sell most of them by the late 2010s, generally at a loss.

COVID and consolidation

The COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 hit SRT’s tenants and their customers hard. Restaurants shut down, seemingly indefinitely; city residents fled for emptier pastures; students and employees started to live life entirely within the confines of Zoom.

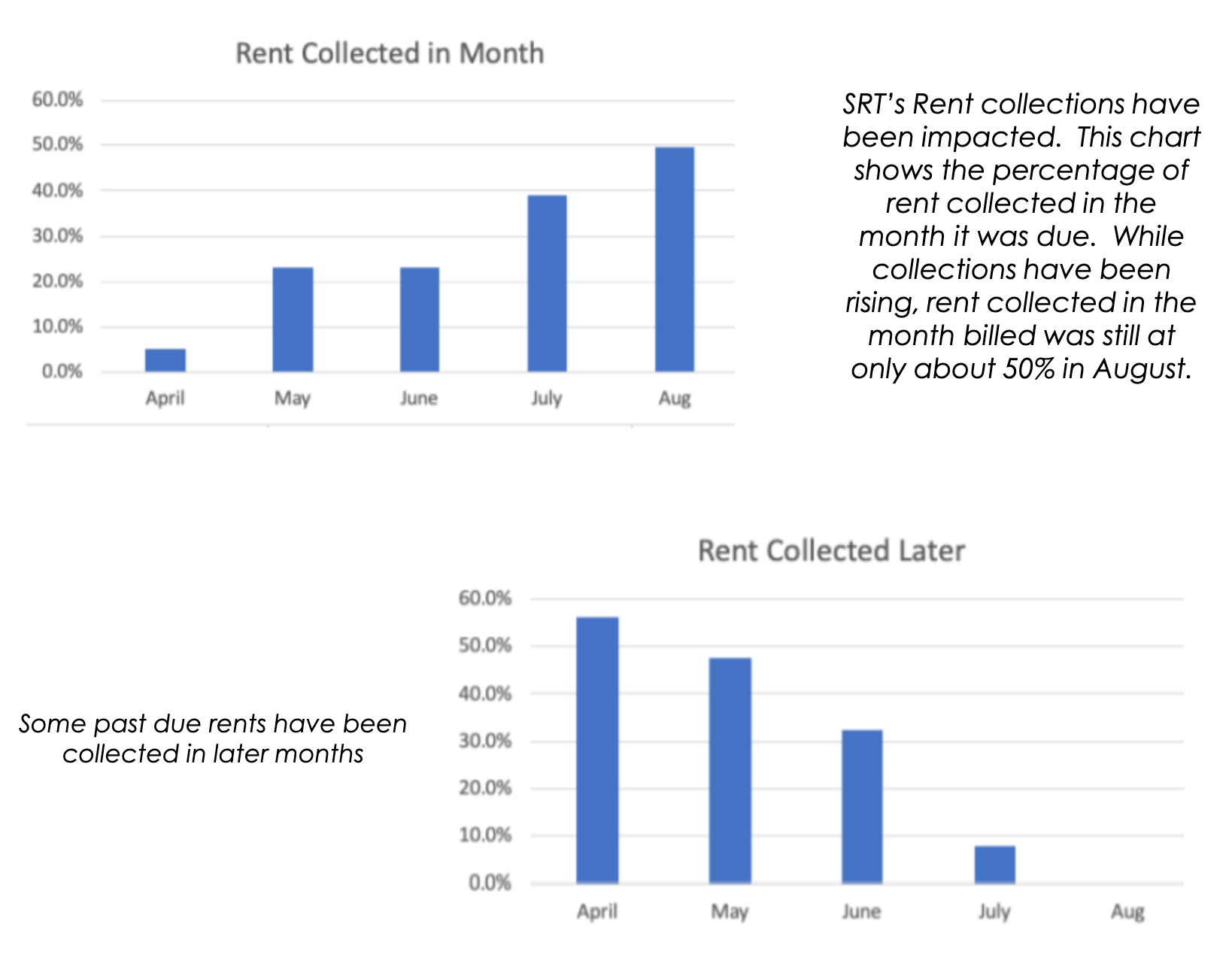

From SRT’s perspective, restaurants that were forced to close or pivot to outdoor/takeout operations stopped or deferred paying rent or requested modifications and other relief. In the month of April 2020, SRT only collected 5% of the rent it had been due, though this would later recover to over 50% by August.

SRT, like many commercial landlords, struggled to collect rent during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: SRT September 2020 newsletter.

In 2020 and 2021, SRT charged $21 million in impairments to its Los Angeles properties due to lower-than-expected rental income, as prospective restaurant tenants pulled out of the projects. The pandemic also delayed SRT’s planned sales of its last two remaining suburban properties in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Hesperia, California.

As human and economic activity started to recover in 2022, SRT was again hit by rising interest rates. Although the company had paid off most of its debt at this point from selling its suburban strip malls, it still had an $18 million floating-rate loan. The interest rate on this loan rose from 4.3% in March 2022 to 8.2% by September 2023; annualized interest expenses subsequently grew from $700,000 to $1.5 million over the same period. This more or less ensured that SRT, which now only had six properties earning $2.6 million a year in rent, would never be able to make a profit again.

On April 1, 2021, Glenborough merged with Chicago-based real estate investment firm L3 Capital, which also specializes in urban and mixed-use properties. There were some apparent synergies: L3 also owned several storefronts in Hayes Valley and elsewhere in San Francisco and Los Angeles. L3 affiliate PUR Management LLC took over as the property manager for the SRT assets. Several L3 executives joined the board of SRT while Batinovich stepped down as CEO after nearly a decade leading the company.

400 Grove Street, one of SRT's properties in San Francisco.

Neglect and writedowns

The recovery (and lack thereof) of SRT’s properties after COVID more or less track citywide trends in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The storefronts close to the heart of Hayes Valley remained fully occupied and earned lucrative rents of $5-8 per square foot per month. Those further away, including one oddly shaped restaurant in the nearby Mid Market neighbourhood, remained vacant.

Meanwhile, Silver Lake in Los Angeles was experiencing a bit of a renaissance, but SRT’s primary tenant there stopped paying rent in late 2023, which resulted in SRT defaulting on its $18 million loan in January 2024. That default bumped the interest rate on the loan to a whopping 13.1%, or nearly $2.4 million.

The last chapter of SRT likely started in August 2023, when its board of directors approved a plan of liquidation and changed the purpose of the company solely to the “wind up our affairs and the liquidation of our assets.” The company engaged Colliers International to try to sell the San Francisco and Los Angeles lots.

SRT’s remaining minority investors have also appeared to stop caring. During the trust’s latest annual meeting of stockholders, only representatives of 26% of shares outstanding showed up in person or by proxy, insufficient to establish a quorum. Incumbent directors mostly affiliated with L3 Capital continued to serve as “holdover” members of the board.

On August 12, 2024, SRT announced that it had reached a deal to sell its San Francisco properties to an affiliate of Texas-based Moran Capital LLC for $10.8 million with closing expected a month later. This price represents a -45% discount to SRT’s last valuation of these properties at $18.7 million, a -51% discount to SRT’s original purchase price of $22 million, and more or less just covers their share of the outstanding SRT loan ($11.1 million). Equity shareholders in SRT get nothing.

Buyer Moran Capital Partners is a privately held real estate management and investment company based in Dallas, Texas. The company has no public profile except for a LinkedIn page indicating it has 2-10 employees. Assuming the deal closes, I wish the new owners the best of luck managing these assets. One silver lining for San Francisco: having acquired these properties for less than half of what they were worth in 2016, the new owners may be willing to offer lower rents that will finally fill some of the empty storefronts on Market Street.

SRT’s Silver Lake, Los Angeles, properties remain on the market and on the company’s books valued at $13.3 million.

Disclaimer: Not financial advice. For entertainment and informational purposes only.