Nvidia's off-balance sheet purchase obligations

Much has been written about whether Nvidia, perhaps one of the most consequential companies of the early 2020s, is worth its astronomical valuation ($3.1 trillion as of July 5, 2024). My contribution to the debate is deep in the accounting weeds. After spending much of the Fourth of July holiday reading Nvidia’s financial statements, what stood out most to me were the company’s substantial future purchase commitments and obligations.

Depending on your perspective, these obligations can hint at either +90% y-o-y growth prospects or aggressive accounting practices to pad revenue and profit margins.

What are purchase obligations?

Purchase obligations, which Nvidia details in footnote 12 of its FY 2025 Q1 financial statements, are basically pinky promises to buy supplies and services in the future. No money has exchanged hands, which makes them distinct from customer deposits otherwise paid to manufacturers to reserve capacity in future periods. This also means they are not included on Nvidia’s balance sheet liabilities.

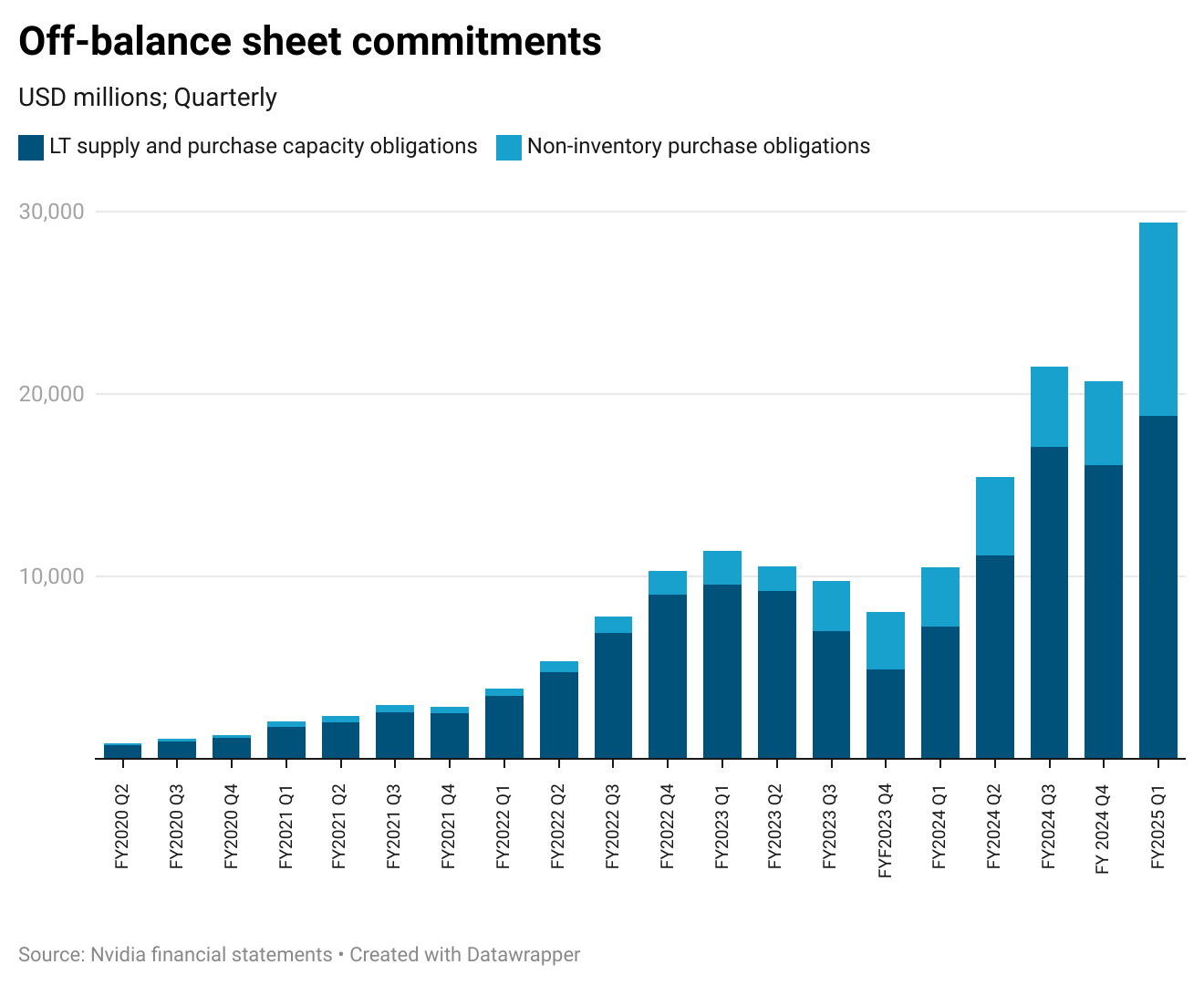

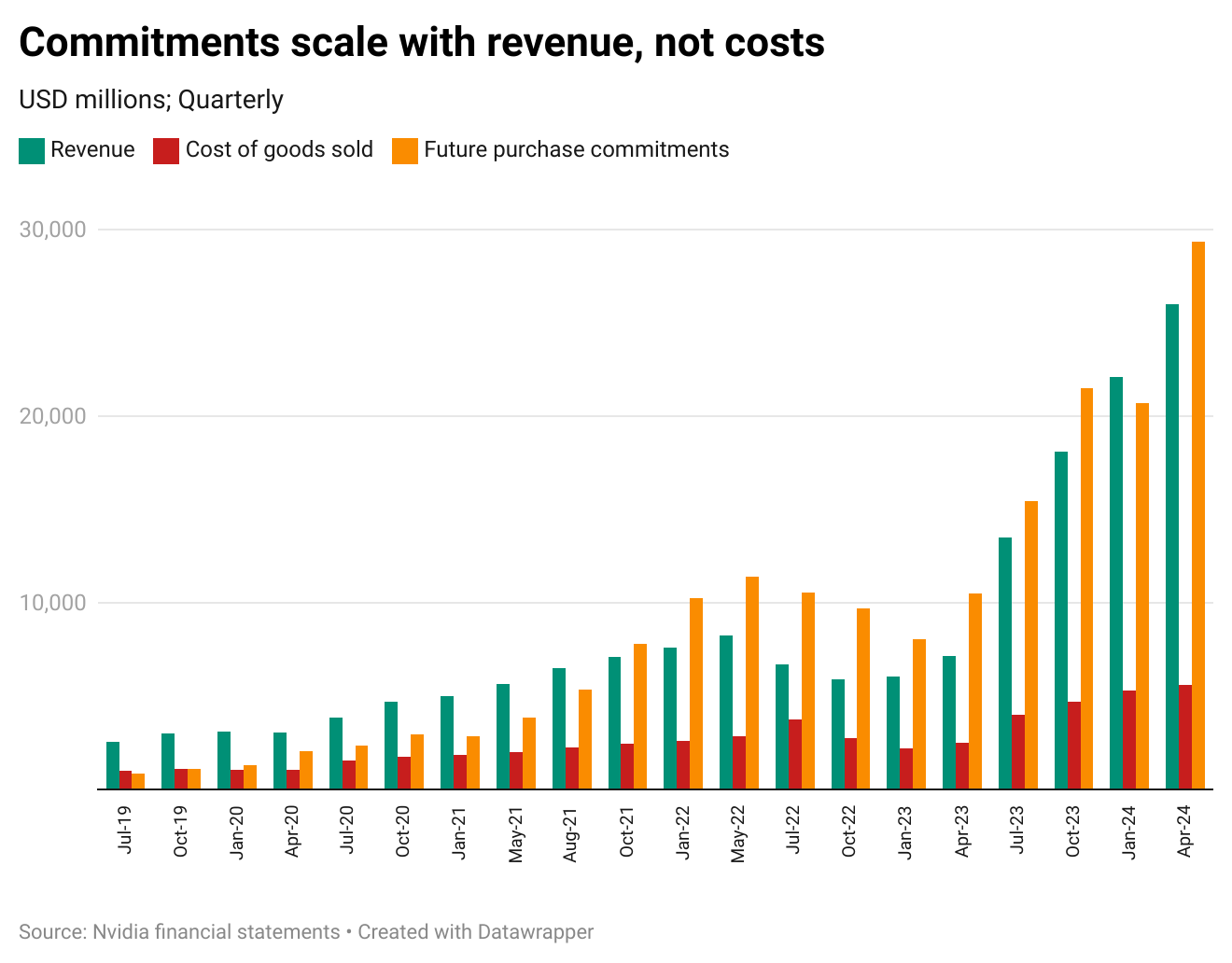

Nvidia’s purchase obligations have exploded in recent quarters alongside its revenues, profits, and share price to nearly $30 billion as of the quarter ending April 28, 2024. Of this, $18.8 billion were for “outstanding inventory purchases and long-term supply and capacity obligations” and $8.8 billion were for “multi-year cloud service agreements.” Nearly $20 billion will be due in FY 2025, less than seven months from today.

The bull view

In the eyes of a (naïve?) bull, this is nothing but good news. Demand for AI chips is through the roof, and Nvidia is simply locking in manufacturing capacity to ensure it will be able to meet the ever-growing demand for GPUs. At a 78% gross profit margin, $18.8 billion in inventory is worth $86 billion in revenue in three quarters, or $114 billion in revenue in FY 2025, a +90% y-o-y increase.

This is in between what you get if you multiply Nvidia’s Q1 revenue by four ($104 billion), and consensus estimates of FY 2025 revenue ($120 billion). If Nvidia can achieve that, Bravo!

Reasons for concern

Examining Nvidia’s purchase commitments and obligations in a longer-term context gives pause for a few reasons. (At this point, it is important for me to caveat that these concerns are in no way accusations of accounting fraud or misrepresentation.)

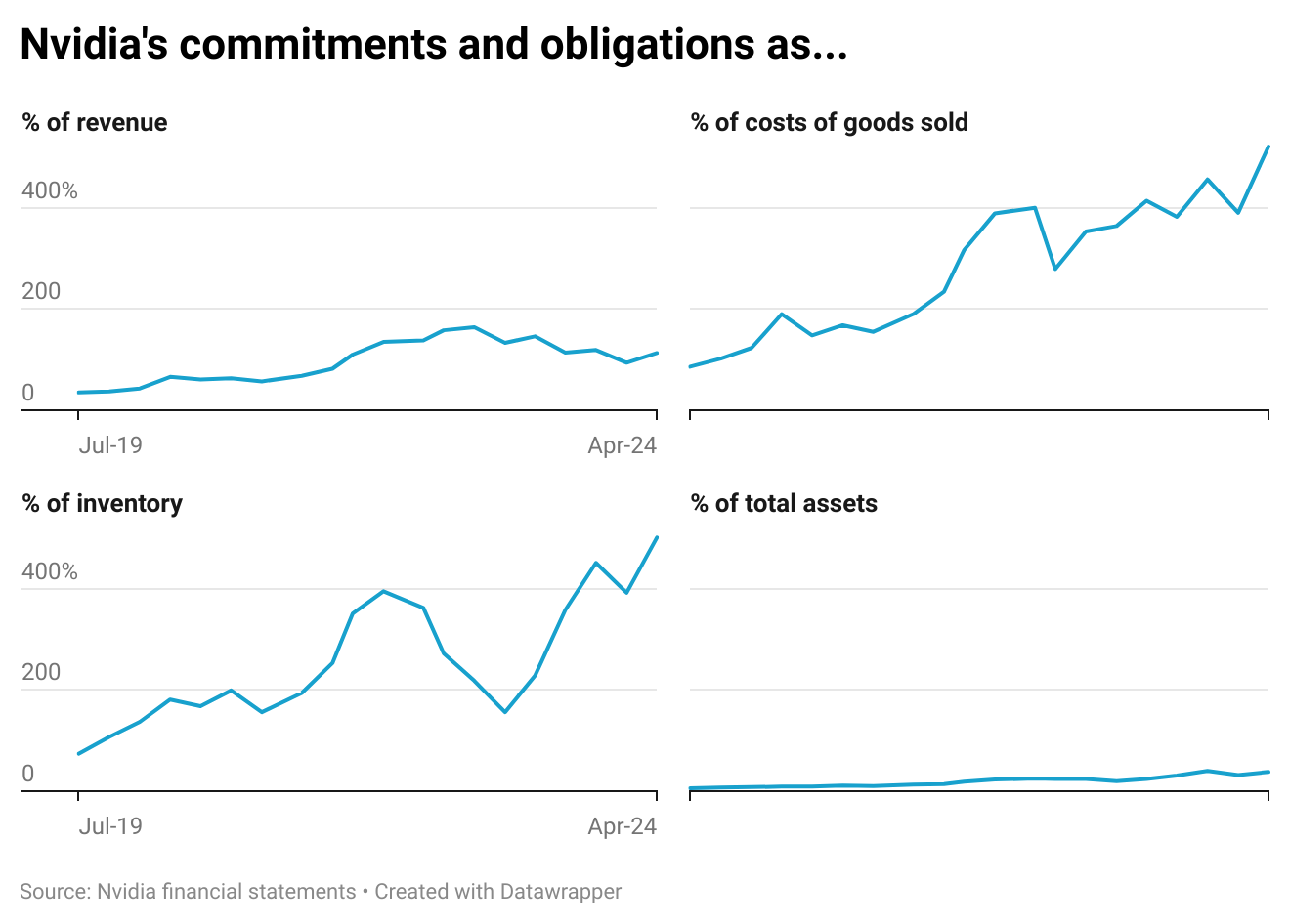

The first is timing. Disclosures of purchase obligations are a relatively new phenomenon for Nvidia, first appearing in FY 2021. Since then, they have gone from barely to extremely material, equivalent to more than 500% of balance sheet inventory and 38% of total assets. This also coincided with Nvidia’s gross profit margins rising from the low-60% range to the high-70% range.

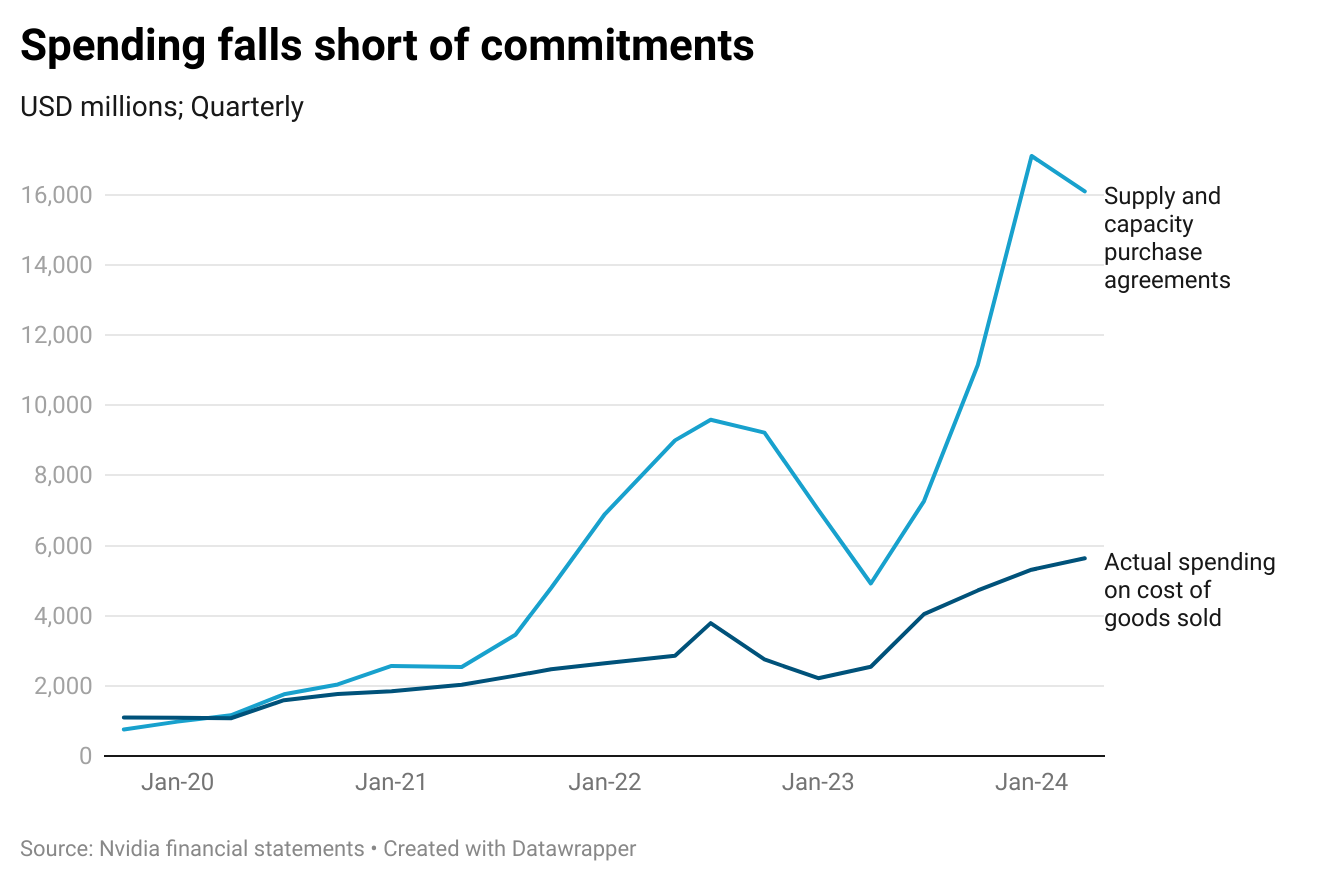

The second is scale. Until 2021, Nvidia’s commitments and purchase obligations grew slowly and remained roughly in line with near-term spending on components and inventory (costs of goods sold). In more recent quarters. However, purchase obligations have grown rapidly and have even exceeded revenues. Especially given Nvidia’s remarkably high gross profit margins, it is odd for inventory purchase commitments to exceed actual sales.

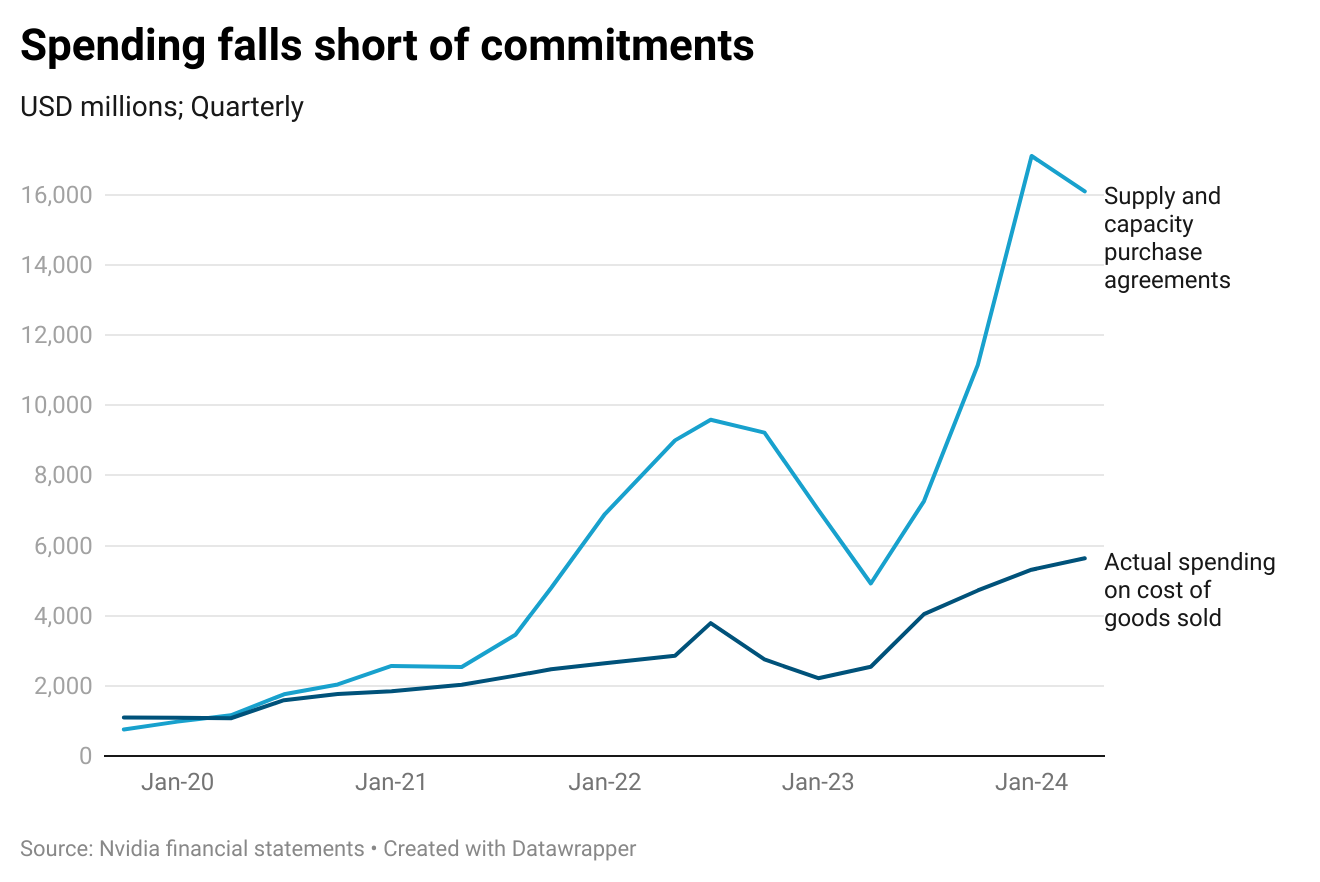

The third is history. Despite Nvidia’s stratospheric sales growth, the company’s actual spending on inventory and capital equipment frequently falls short of earlier commitments. Nvidia started Q1 2025 with $16.1 billion in “long-term supply and purchase capacity obligations,” spent $5.6 billion on COGS, and then committed another $8.3 billion in additional spending to end the quarter with $18.8 billion in purchase obligations.

Nvidia says that “in certain instances, these agreements are cancellable, able to be rescheduled, and adjustable for our business needs prior to placing firm orders.” It certainly appears that many earlier purchase obligations have been rescheduled further into the future.

What does $18.8 billion in purchase obligations represent? TSMC reported $18.5 billion in revenues in its first quarter ending March 2024. Of this, 37%, or $6.8 billion came from its 5-nanometer process wafers which include Nvidia’s hugely popular Hopper H100 GPUs ($28,999.99 on Amazon). Nvidia’s purchase obligations is equivalent to almost all of TSMC’s 5-nm production capacity over the past year.

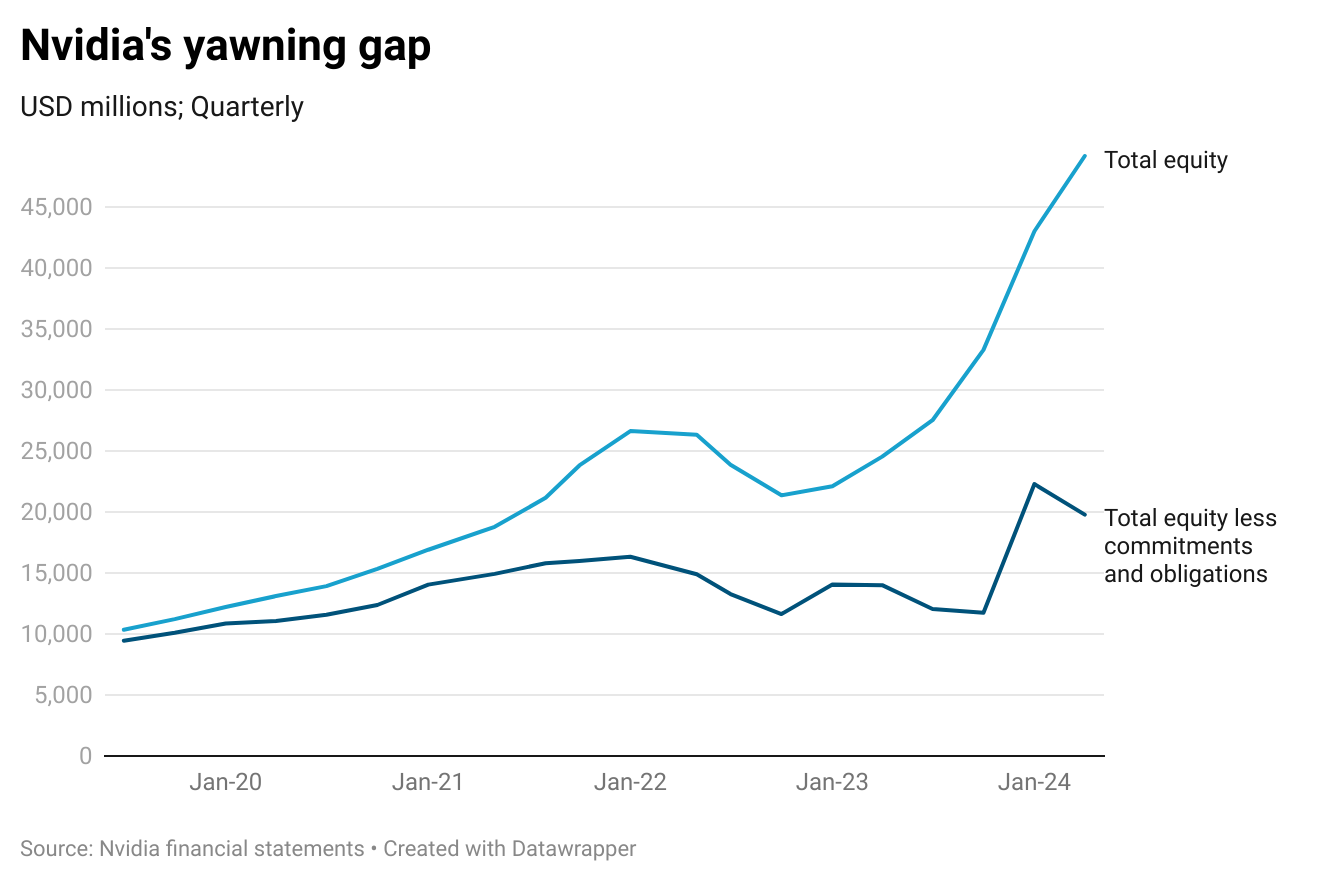

Finally, there’s valuation. If we add Nvidia’s total purchase commitments and obligations to its, we see a picture of a company that is far more levered, less liquid, and even more overvalued than it currently appears. Adjusted for off-balance sheet commitments, Nvidia’s shareholder equity as of April sat at just $19.8 billion, less than half that of the reported $49.1 billion. That would value the company at 160x price/book!

Implications and speculations

As outsiders we cannot know what these trends in Nvidia’s purchase obligations represent without speaking to the company’s purchasing department and reading the exact wording of the agreements. A skeptical bear may nevertheless think of the following implications and hypotheses.

Nvidia could be on the hook for substantial cancellation penalties and/or inventory write-downs should chip demand fall even moderately short of +100% y-o-y growth expectations. This happened recently in Q2 FY 2023, when Nvidia took a $1.2 billion charge, equivalent to 40% of revenue, due to “inventory on hand … and inventory purchase obligations in excess of our current demand projections, and cancellation and underutilization penalties.”

More strategically, Nvidia may be signing future purchase commitments in exchange for lower prices from its suppliers today. This would allow Nvidia to report higher-than-average gross profit margins in current periods in exchange for lower margins in the future. Near-term profits are boosted at the risk of lower profits and inventory provisions in the future.

Nvidia may also be engaging in some form of “boomerang” transactions, especially related to the "$8.8 billion of multi-year cloud service agreements" portion of its purchase obligations. One can imagine a situation where Nvidia sells more-than-necessary chips to cloud computing customers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure, with an implicit agreement to buy back a portion of that capacity.

The last speculation reminds me of the curious case of MicroStrategy during the Dot-Com bubble. In the second half of 1999, MicroStrategy aggressively signed mutually purchase agreements with industry peers NCR and Exchange Applications, allowing both parties to report revenue growth even as money was simply flowing from Party A to Party B back to Party A. MicroStrategy eventually got into trouble with the SEC for inappropriately recognizing revenues early.

Nvidia’s behavior does not look nearly as egregious. But it is worth reflecting on previous tech bubbles as we try to make sense of ongoing ones.