The weird afterlife of Wish.com

Originally published on Substack.

Disclosure: I am long ContextLogic (NASDAQ: LOGC).

Before Shein and Temu (and Amazon Haul), there was Wish.com. Founded in San Francisco in 2010 and listed on the NASDAQ in 2020, Wish.com embodied the gamified discounting, hyper-targeted weirdness, mobile-first approach to online shopping that we have all since developed a love/hate relationship with: $5 headphones, $9 sex toys, and $2 bundles of worms alongside generic household goods and clothing. Allow 6-8 weeks for delivery via container ship from China.

Wish.com’s apps and website are still up as of February 2025, but this user tried multiple times to place an order (for this adorable Easter rabbit wreath) and was unable to do so. “Sorry, something went wrong,” says a plain red sans-serif font against a white HTML page.

The error page and payment failure hint at the slow decay of the website. Wish.com’s current owner Qoo10 was ordered by courts in Singapore to be liquidated in November 2024 after merchants complained that they hadn’t been paid for months. Qoo10 stopped accepting payments in September 2024.

It’s a rather unglamorous death for a company whose logo once graced the jerseys of the Los Angeles Lakers, and was widely lauded as a $21 billion Amazon challenger ushering in a new age of internet retail.

A brief history

Others have done a great job of documenting Wish.com’s rise and fall; I’ll direct you to these reports from the New York Times and Speedwell Research. The short version is this:

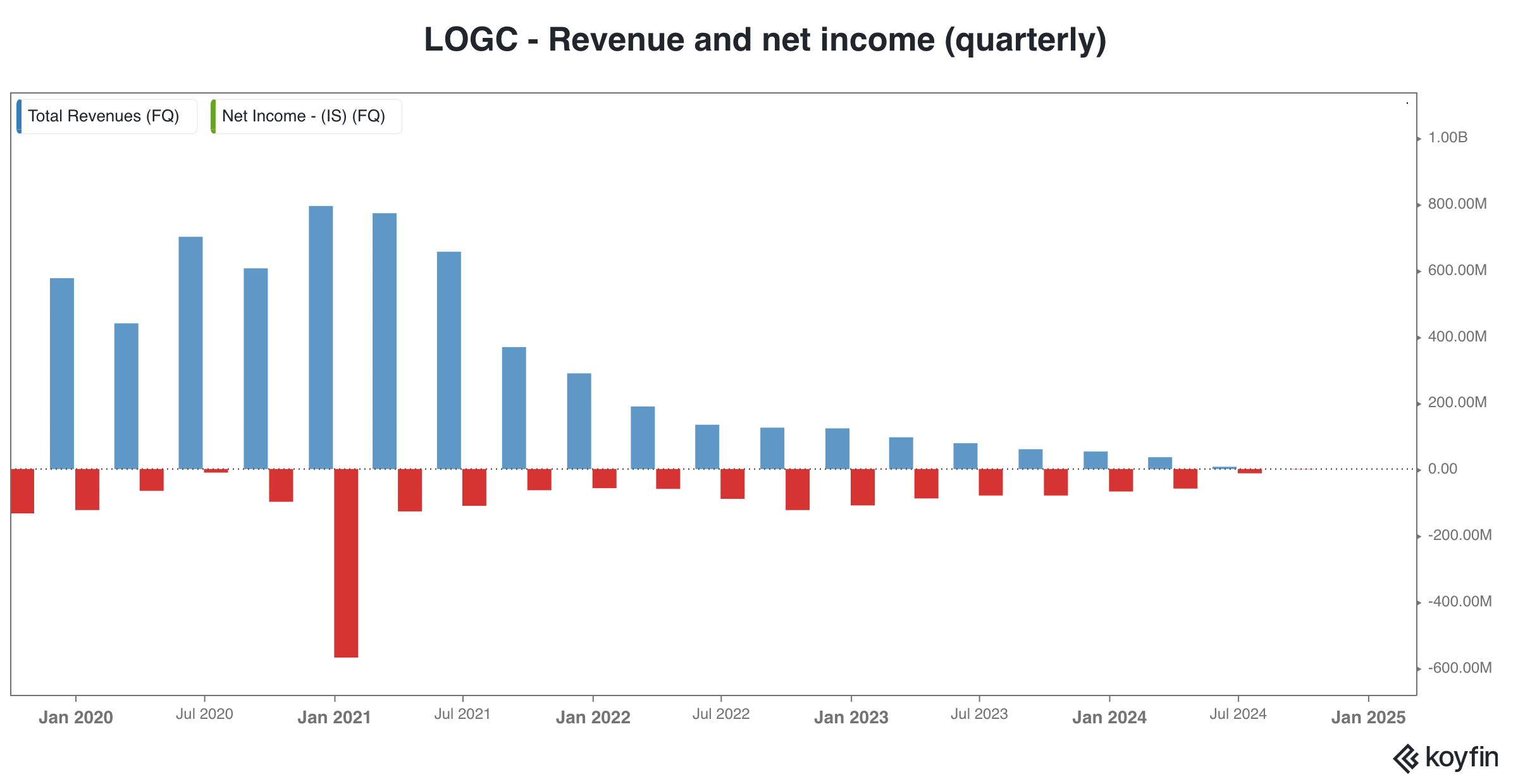

Wish.com’s parent company ContextLogic listed on NASDAQ in 2020 and surged to a peak valuation of $21 billion on $2.5 billion in revenues during the pandemic-induced online shopping boom in early 2021. Then sales and active users began to fall, customer complaints and regulatory pressure rose, and the stock price fell even more. In February 2024, ContextLogic sold Wish.com to South Korean e-commerce platform Qoo10 for $173 million. Qoo10 itself filed for bankruptcy in Singapore later that year.

When ContextLogic sold Wish.com to Qoo10, it managed to hold onto its cumulative $2.7 billion of net operating losses (NOLs). Wish.com never generated a profit, but US tax laws allow companies to carry forward NOLs from one tax year and use them to offset taxable profits in future years, subject to some restrictions. The official reason this is allowed is so that companies with lumpy profits aren’t double taxed.

For a while, the answer to the question of “How much would you pay for a tax asset” was basically zero for ContextLogic. On February 25, 2025, ContextLogic announced an up to $150 million investment by BC Partners that will support its revised strategic goal of “acquiring and/or building one or more operating businesses” to monetize its NOLs.

My tax assets will live on

How exactly do you monetize an NOL? An NOL functions much like a personal income tax deduction; you use it to reduce your taxable income. At the current federal corporate income tax rate of 21%, ContextLogic’s $2.8 billion in NOLs could save a company $588 million in undiscounted future tax payments. If Trump cuts taxes, the NOLs would be worth less.

The IRS does not make tax avoidance easy. ContextLogic faces a few considerations and constraints.

First is that the NOLs can only be applied to income that was generated substantially by the same business that generated the losses. This is the “continuity of business enterprise” theory and was established explicitly to prevent profitable companies from acquiring random unprofitable companies to reduce their tax bill. What “same business” means here is unclear (to me, at least); legal precedence has largely focused on acquiring companies continuing to operate the business line that originally generated the losses. ContextLogic’s previous business could mean something as specific as “discount e-commerce platform” or as broad as “technology company.”

Second is that there cannot be major changes to ContextLogic’s ownership structure; Section 382 of the Internal Revenue Code imposes significant restrictions on the use of NOLs if any major shareholder (of more than 5%) increases or decreases their shareholding by 50 percentage points. This again is to prevent profitable companies from acquiring random unprofitable companies to reduce their tax bill. If there is such a change, ContextLogic would only be able to use a small proportion of its NOLs every year.

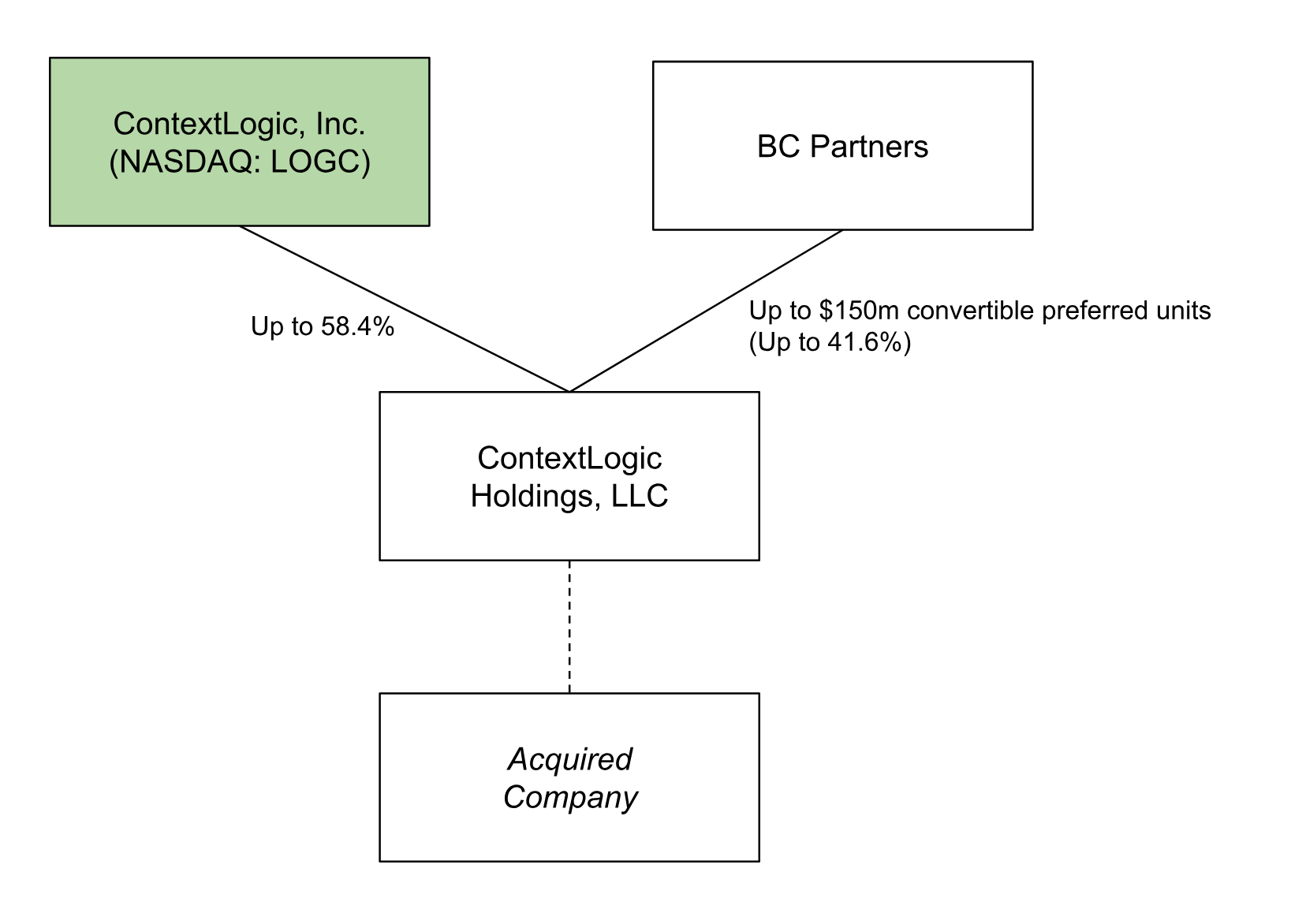

This restriction is perhaps why BC Partners’ $150 million was structured as an investment in convertible preferred units of a subsidiary of ContextLogic, so as to not affect the ownership structure of the parent company with the NOLs. ContextLogic itself also has a Tax Benefits Preservation Plan to discourage any single shareholder from acquiring more than 4.9% of the company.

Whatever company ContextLogic merges with will also need to be generating sufficient taxable profits to make ContextLogic’s NOLs actually useful, especially as $900 million out of the $2.8 billion expire between 2030 and 2037. This probably means something that generates at least tens to hundreds of millions in annual profits. They must also have a distributed enough ownership structure such that no single shareholder ends up with more than 5% of the surviving entity, triggering Section 382.

As a shell company ContextLogic is in some ways the anthesis of a SPAC. Rather than taking a minority stake in an unprofitable startup, ContextLogic needs to take a majority stake in a highly profitable company.

Hunting for profits

Armed with up to $300 million, ContextLogic and BC Partners are now on the hunt for a company to buy. The list of prospects is likely to be short; one commentator on VIC suggests it could be a bank, consumer finance, or insurance company due to their high taxable earnings and low valuation multiples. We’re looking for companies that:

- Earn pretax profits of at least $50 million.

- Want to reduce their tax bill (and so pay effective tax rates of at least 20%).

- At a “reasonable” valuation (less than $400 million in market cap to start).

- Do not have any significant shareholders of more than 5%.

A simple screen of public companies reveals a total of 18 companies that meet the first three criteria. There may be more companies available on the private side.

ContextLogic today is on a hunt for profits, a commodity that has otherwise been in short supply among Silicon Valley startups over the past decade. Its corporate address moved from a skyscraper in downtown San Francisco to a virtual mailbox in an industrial neighborhood of Oakland. Depending on your discount rate, ContextLogic’s NOLs are worth at least as much as what it sold Wish.com for. If ContextLogic and BC Partners pull find a suitable partner, it will already have accomplished more for its investors than other one-hit wonders, somehow salvaging value failure at scale.

Disclaimer: Not financial advice. For entertainment and informational purposes only.